|

Peremennye Zvezdy (Variable Stars) 26, No. 6, 2006 Received 3 May; accepted 1 August.

|

Article in PDF |

GSC 7672:2238: a binary system near the Delta Scuti star AI Vel

P.C.R. Pereira1, J.M. Santos-Junior1, D.A. Pilling2, W.S. Cruz1

- Fundação Planetário da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro,

Rua Vice-Gov. Rubens Berardo 100, Rio de Janeiro, RJ 22451-070,

Brazil; e-mail: pcpereira@pcrj.rj.gov.br,

jorgejunior@pcrj.rj.gov.br, wcruz@rio.rj.gov.br

- Observatório Nacional/CNPq, Rua General José Cristino, 77, Rio de Janeiro, RJ 20920, Brazil; e-mail: diana@on.br

|

We report the results of a photometric and

spectroscopic study of an eclipsing binary star in the field of

the Delta Scuti variable AI Vel. Time-series CCD photometry was

performed allowing almost complete phase coverage. Our period

search gave an orbital period of 0 |

1. Introduction

Since 2001, we are conducting systematic monitoring of High

Amplitude Delta Scuti (HADS) stars aiming to confirm/improve

period determinations and looking for pulsational period

variations and microvariability. In the course of a photometric

campaign on AI Vel, we detected a short-period binary system.

Initially used as a check star during the photometric monitoring

of AI Vel, GSC 7672:2238

(

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ) turned out to

be variable as soon as we started the project. Although no

previous variability detection could be found in the SIMBAD

(operated at CDS, Strasbourg, France) and GCVS (Kholopov et al.

1998) databases, this star is present in the ASAS-3 catalog

(Pojmanski 2003) as an eclipsing variable with a period of about

12 hours. We collected more data trying to confirm and classify

the observed variability using one of the telescopes (

) turned out to

be variable as soon as we started the project. Although no

previous variability detection could be found in the SIMBAD

(operated at CDS, Strasbourg, France) and GCVS (Kholopov et al.

1998) databases, this star is present in the ASAS-3 catalog

(Pojmanski 2003) as an eclipsing variable with a period of about

12 hours. We collected more data trying to confirm and classify

the observed variability using one of the telescopes (![]() )

located at the Rio de Janeiro Planetarium. In addition, we

acquired a single spectrum to help clarifying the situation. The

light curve has a morphology typical of Algol-type variables.

)

located at the Rio de Janeiro Planetarium. In addition, we

acquired a single spectrum to help clarifying the situation. The

light curve has a morphology typical of Algol-type variables.

The Algols are close interacting binary stars. They consist of a B-A main sequence primary star and an F-K giant or subgiant secondary. In general, the star eclipsed at the primary minimum is the more massive component, very similar to Main Sequence stars. This picture gave rise to the well-known Algol paradox (an unevolved more massive primary accompanied by an evolved low-mass secondary).

Mass transfer (due to the secondary star's evolution, which

expands to its Roche lobe limit) is likely to occur in a permanent

way in the long-period Algol systems (![]() days) giving rise to a

stationary disk, while in the short-period Algols (

days) giving rise to a

stationary disk, while in the short-period Algols (![]() days),

accretion is less stable. The primary star is very large in

comparison with the binary's separation, and the transferred gas

stream impacts its surface straight off. As a result, very complex

structures can arise, such as a transient accretion disk or even a

less homogeneous structure (for

days),

accretion is less stable. The primary star is very large in

comparison with the binary's separation, and the transferred gas

stream impacts its surface straight off. As a result, very complex

structures can arise, such as a transient accretion disk or even a

less homogeneous structure (for ![]() days), called an accretion annulus. The accreted material can be observed at UV

and visible light, and the H

days), called an accretion annulus. The accreted material can be observed at UV

and visible light, and the H![]() line is frequently used as

diagnostic of mass transfer (Albright

line is frequently used as

diagnostic of mass transfer (Albright ![]() Richards 1996;

Richards, Jones,

Richards 1996;

Richards, Jones, ![]() Swain 1996, and references therein.)

Swain 1996, and references therein.)

In the present paper, we report on photometric and spectroscopic characteristics of GSC 7672:2238.

2. Observations and data reduction

We carried out our time-series unfiltered differential CCD

photometry during two seasons, in 2002 and 2003. We observed

GSC 7672:2238 with a SBIG ST7E or ST8E thermoelectrically cooled

CCD camera (![]() ,

,

![]() pixels) attached to the Meade

LX200

pixels) attached to the Meade

LX200 ![]() Schmidt-Cassegrain (F/6.3) telescope of the Rio de Janeiro Planetarium

Foundation in south-east Brazil. For the useful field of view,

these sets gave

Schmidt-Cassegrain (F/6.3) telescope of the Rio de Janeiro Planetarium

Foundation in south-east Brazil. For the useful field of view,

these sets gave ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively.

, respectively.

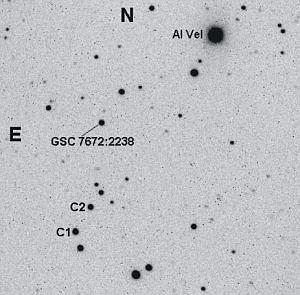

Our data reductions made use of the Image Reduction and Analysis Facility (IRAF) software. All images were dark-subtracted and flat-field-corrected. The photometric uncertainty was estimated from the standard deviation of the magnitude difference between the comparison (C1) and check (C2) stars.

GSC 7672:1538 (

![]() ,

,

![]() , 11

, 11![]() 6

6 ![]() ) was used as

the comparison star and GSC 7672:1586

(

) was used as

the comparison star and GSC 7672:1586

(

![]() ,

,

![]() , 11

, 11![]() 8

8 ![]() ), as the check

star. Since the angular distances of all the stars in the field

were small, we did not introduce any correction for differential

extinction. The estimated differential-photometry accuracy ranged

from 0

), as the check

star. Since the angular distances of all the stars in the field

were small, we did not introduce any correction for differential

extinction. The estimated differential-photometry accuracy ranged

from 0![]() 005 to 0

005 to 0![]() 012. The finding chart is presented in

Fig. 1.

012. The finding chart is presented in

Fig. 1.

The log of observations is given in Table 1.

![]() is the integration time,

is the integration time, ![]() the number of frames in

each run,

the number of frames in

each run, ![]() C1-C2

C1-C2![]() the mean values of C1-C2, to check

long-term constancy, and the last column lists the uncertainty in

the photometry.

the mean values of C1-C2, to check

long-term constancy, and the last column lists the uncertainty in

the photometry.

| Date | length | ||||

| (s) | (hours) | ||||

| Apr. 01, 2002 | 20 | 156 | 4.1 | 0.428 | 0.010 |

| Apr. 02, 2002 | 20 | 217 | 5.5 | 0.430 | 0.010 |

| Apr. 17, 2002 | 20 | 191 | 4.3 | 0.425 | 0.009 |

| Apr. 18, 2002 | 20 | 202 | 4.8 | 0.429 | 0.012 |

| Jan. 08, 2003 | 60 | 153 | 4.5 | 0.430 | 0.005 |

| Jan. 09, 2003 | 60 | 169 | 5.7 | 0.430 | 0.007 |

| Feb. 03, 2003 | 60 | 210 | 6.0 | 0.425 | 0.009 |

| Feb. 05, 2003 | 60 | 98 | 3.8 | 0.433 | 0.007 |

| Feb. 06, 2003 | 60 | 82 | 3.4 | 0.427 | 0.008 |

| Feb. 10, 2003 | 60 | 176 | 4.3 | 0.424 | 0.005 |

| Feb. 12, 2003 | 60 | 98 | 2.2 | 0.424 | 0.006 |

| Feb. 13, 2003 | 60 | 94 | 2.4 | 0.429 | 0.012 |

| Feb. 19, 2003 | 60 | 90 | 4.1 | 0.424 | 0.005 |

| Feb. 25, 2003 | 60 | 216 | 5.8 | 0.435 | 0.007 |

| Mar. 01, 2003 | 60 | 107 | 2.4 | 0.424 | 0.006 |

| Mar. 07, 2003 | 40 | 120 | 2.3 | 0.429 | 0.008 |

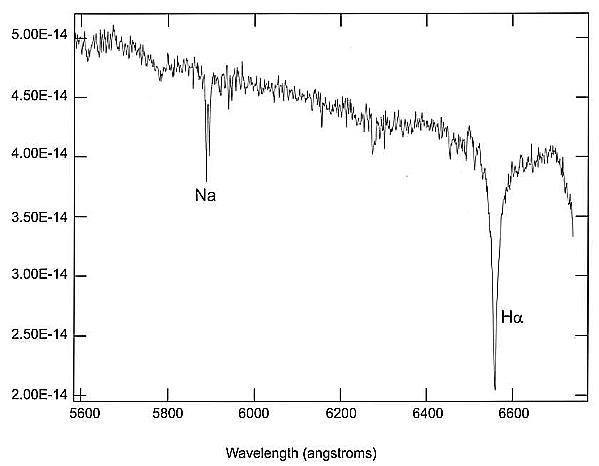

In addition, we made a single spectroscopic observation of GSC

7672:2823 with the 1.6 m Perkin-Elmer telescope located at the

Pico dos Dias Observatory, operated by the CNPQ/National

Laboratory of Astrophysics, Minas Gerais, Brazil, on April 17,

2002. A medium-resolution spectrum in the 5700-6750Å range

was obtained in the Cassegrain focus with a 900 lines/mm grating.

The spectrum was subjected to wavelength and flux calibration

using IRAF tasks. LIT 3218 was used as the spectrophotometric

standard to perform flux calibration (Hamuy et al. 1992, Hamuy et

al. 1994). We used a He-Ar lamp to calibrate in ![]() , the

integration time was 20 minutes.

, the

integration time was 20 minutes.

3. Results and analysis

3.1. Photometry

We determined CCD times of the primary minimum using the Kwee ![]() van Woerden method (Kwee

van Woerden method (Kwee ![]() van Woerden 1956), which is suitable

for symmetrical light curves. Table 2 gives the heliocentric times

of primary minima. Epochs and O-C values were computed with

respect to the linear ephemeris given in eq. (1).

van Woerden 1956), which is suitable

for symmetrical light curves. Table 2 gives the heliocentric times

of primary minima. Epochs and O-C values were computed with

respect to the linear ephemeris given in eq. (1).

| HJD (error) | Epoch | O-C |

| 2452382.5037(1) | 0 | -0.00039 |

| 2452383.4764(2) | 1 | 0.0004 |

| 2452696.4188(2) | 323 | -0.000002 |

After the least-square fit to the data given in Table 2, we found the following preliminary ephemeris for the primary minima:

We made a further analysis of the light curve of GSC 7672:2238 using two different methods to search for periods.

First, we applied the classical phase-dispersion-minimization

(PDM) technique (Stel-lingwerf 1978), which is very useful when

the light curve is highly non-sinusoidal. This method folds the

data on groups of trial frequencies and constructs phase-folded

data for each of them. After defining the number and width of bins

over the generated diagram, the variance for each bin is

calculated. Figure 2 shows the PDM periodogram. The strongest

(deepest) signal is ![]() hours (0

hours (0![]() 9626), it has the

smallest variance.

9626), it has the

smallest variance.

Another period search was performed with the ANOVA method, which

uses periodic orthogonal polynomials to fit data. Evaluation of

the fit is made by analysis of variance (ANOVA) statistic

(Schwarzenberg-Czerny 1996). This method improves strongly the

signal detection and is very effective damping alias signals. The

ANOVA periodogram is displayed in Fig. 3 and shows the main peak

at

![]() (0

(0![]() 9719), which is in nice agreement with

the value found from the O-C analysis.

9719), which is in nice agreement with

the value found from the O-C analysis.

Additional analysis was done with the ASAS-3 data using the PDM

and ANOVA methods. We found strong signals for both methods at

![]() (0

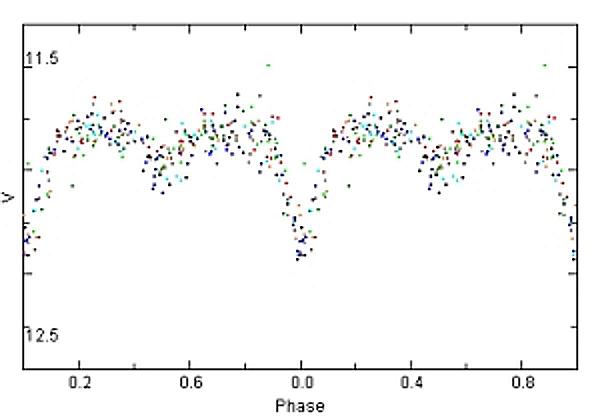

(0![]() 9720). Figure 4 shows the phase-folded

diagram with respect to

9720). Figure 4 shows the phase-folded

diagram with respect to

![]() for the ASAS-3 data,

indicating that the 12-hour period is probably wrong.

for the ASAS-3 data,

indicating that the 12-hour period is probably wrong.

|

Fig. 4.

The phase-folded diagram for GSC 7672:2238 using the ASAS-3 data for

|

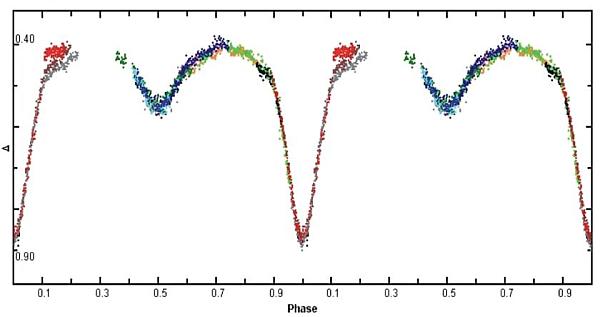

Figure 5 shows the phase-folded diagram (for the data obtained by us) with respect to eq. (1). We note a strong modulation with two minima per cicle, probably related to the orbital motion of a binary system consisting of deformed components. Both primary and secondary eclipses are V-shaped and centered at phases 0.0 and 0.5 respectively, indicating a circular orbital motion.

|

Fig. 5.

The unfiltered phase plot for GSC 7672:2238 with

|

The primary eclipse is fainter by about 0![]() 35 than the secondary

one. The light curve shows a morphology typical of Algol systems.

An interesting characteristic of the light curve is a larger

scatter during maxima (centered at

35 than the secondary

one. The light curve shows a morphology typical of Algol systems.

An interesting characteristic of the light curve is a larger

scatter during maxima (centered at ![]() =0.7). The same picture

is seen during secondary eclipses.

=0.7). The same picture

is seen during secondary eclipses.

From the same figure, we note obvious changes around phases 0.1 to

0.2, when the brightness had increased slowly by about 0![]() 06 in

10 days. The gray, brown, and red colors are associated to dates

Feb. 25, 2003, Mar. 1, 2003, and Mar. 7, 2003, respectively. Such

behavior can be explained in terms of mass transfer from the

lobe-filling secondary star. An impact zone (over the primary,

facing the secondary) would produce the brightening just after the

primary eclipse. Due to the close orbit, the impact zone would be

strongly asymmetric and plump. Eventually, an extended region can

be formed which could be a potential source of continuum. Besides

the observed variability at

06 in

10 days. The gray, brown, and red colors are associated to dates

Feb. 25, 2003, Mar. 1, 2003, and Mar. 7, 2003, respectively. Such

behavior can be explained in terms of mass transfer from the

lobe-filling secondary star. An impact zone (over the primary,

facing the secondary) would produce the brightening just after the

primary eclipse. Due to the close orbit, the impact zone would be

strongly asymmetric and plump. Eventually, an extended region can

be formed which could be a potential source of continuum. Besides

the observed variability at ![]() , this process can

explain the larger scatter (around

, this process can

explain the larger scatter (around ![]() =0.7) mentioned above.

=0.7) mentioned above.

Another possibility is the presence of photospheric spots over the secondary. It is well known that enhanced magnetic fields in the convective envelopes of such stars are common. They are responsible for strong microwave, X-ray, and visible activity in short-period Algols.

3.2. Spectroscopy

Figure 6 shows the optical spectrum obtained on April 17, 2002.

The time of observation was 22:00 UT corresponding to ![]() =0.9,

just before the primary eclipse. At this phase, if a disk exists,

we expect to find an emission H

=0.9,

just before the primary eclipse. At this phase, if a disk exists,

we expect to find an emission H![]() line. In our spectrum, we

see a strong absorption H

line. In our spectrum, we

see a strong absorption H![]() Balmer line. Another strong

feature is the absorption sodium line, probably associated to the

cooler secondary star. The first feature (the H

Balmer line. Another strong

feature is the absorption sodium line, probably associated to the

cooler secondary star. The first feature (the H![]() absorption

line) is common in other short-period systems such as V505 Sgr,

absorption

line) is common in other short-period systems such as V505 Sgr,

![]() Lib, AI Dra, TW Cas, and TV Cas, all with periods shorter

than 2

Lib, AI Dra, TW Cas, and TV Cas, all with periods shorter

than 2![]() 4. Only a weak single-peaked emission is found in the

difference spectra (modelling and subtracting the spectrum of the

photospheres of the components) of V505 Sgr and

4. Only a weak single-peaked emission is found in the

difference spectra (modelling and subtracting the spectrum of the

photospheres of the components) of V505 Sgr and ![]() Lib

(Richards & Albright 1999). The same authors show that this

feature (weak or absent H

Lib

(Richards & Albright 1999). The same authors show that this

feature (weak or absent H![]() in emission) is permanent at all

orbital phases for systems with

in emission) is permanent at all

orbital phases for systems with

![]() .

.

In this sense, GSC 7672:2238 shows a spectrum which is typical of

short-period Algols with transient or absent disks. The primary

star should be very large in comparison to the binary's

separation, and the mass eventually transferred has no space to

form classical accretion structures. We remember that the spectrum

had been acquired about one year earlier than the variability at

![]() was detected.

was detected.

4. Conclusions

We have observed the poorly studied eclipsing binary system GSC

7672:2238. Despite the small number of times of minimum, we found

![]() using independent methods, which gave

consistent values. The amount of data and the behavior of the

light curve led us to interpret this modulation as related to the

orbital motion of a short-period Algol.

using independent methods, which gave

consistent values. The amount of data and the behavior of the

light curve led us to interpret this modulation as related to the

orbital motion of a short-period Algol.

We found strong photometric evidence for phase-related phenomena

(at ![]() ) probably associated with a long-term mass

transfer (about 10 days) from a lobe-filling secondary star.

Another possible source are photospheric spots.

) probably associated with a long-term mass

transfer (about 10 days) from a lobe-filling secondary star.

Another possible source are photospheric spots.

The single spectrum acquired (at ![]() ) showed a strong

H

) showed a strong

H![]() absorption line, which is indicative of transient or

even absent disk structure. This characteristic is frequently

found in the short-period systems(

absorption line, which is indicative of transient or

even absent disk structure. This characteristic is frequently

found in the short-period systems(

![]() ), which have small

binary separations and large primary stars. As a result, the mass

transfer impacts the primary star avoiding formation of a stable

accretion disk. In fact, the gas transferred may graze the surface

of the primary star and spread matter into a transient structure.

The resulting "plump" structure could be the source of continuum

excess after primary eclipses, observed at Feb. 25, 2003, Mar. 1,

2003, and Mar. 7, 2003 and of the increased scatter at

), which have small

binary separations and large primary stars. As a result, the mass

transfer impacts the primary star avoiding formation of a stable

accretion disk. In fact, the gas transferred may graze the surface

of the primary star and spread matter into a transient structure.

The resulting "plump" structure could be the source of continuum

excess after primary eclipses, observed at Feb. 25, 2003, Mar. 1,

2003, and Mar. 7, 2003 and of the increased scatter at ![]() .

.

In order to characterize GSC 7672:2238 with better certainty, multicolor photometry would be of great importance. In particular, a good coverage could help to identify the source of variability near the primary eclipse.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Fernando Vieira for suggestions and Francisco Xavier for time allocation in LNA. We thank the equipment support provided by VITAE Foundation. Finally, we are grateful to the referee for corrections and useful comments and suggestions.

References:

Albright, G. E. and Richards, M. T., 1996, ApJ, 459, L99

Hamuy, M., Suntzeff, N. B., Heathcote, S. R., Walker, A. R., Gigoux, P., and Phillips, M. M., 1994, PASP, 106, 566

Hamuy, M., Walker, A. R., Suntzeff, N. B., Gigoux, P., Heathcote, S. R., Phillips, M. M., 1992, PASP, 104, 533

Kholopov, P. N. et al. 1998, Combined General Catalogue of Variable Stars, Edition 4.1 (II/214A)

Kwee, K. K. and van Woerden, H., 1956, BAN, 12, 327

Pojmanski, G., 2003, Acta Astronomica, 53, 341.

Richards, M.T. and Albright, G.E., 1999, ApJ, Suppl. Ser., 123, 537

Richards, M. T., Jones, R. D., and Swain, M. A., 1996, ApJ, 459, 249

Schwarzenberg-Czerny, A., 1996, ApJ, 460, L107

Stellingwerf, R. F., 1978, ApJ, 224, 953